Denver punter Britton Colquitt is hoping, praying even, that the Broncos are able to start Super Bowl 50 on Sunday against Carolina much better than they did in the title game two years ago against Seattle.

The Broncos’ 43-8 blowout loss to the Seahawks that day infamously, sloppily began with a snap over the head of quarterback Peyton Manning and into the end zone, resulting in a two-point safety for Seattle.

That brought Colquitt onto the field—with just 12 seconds elapsed—to kick the ball away to the Seahawks.

This Sunday against the Panthers, Colquitt would much prefer his first appearance to be in his role of holder for an extra-point kick following a Broncos’ touchdown.

He knows, however, that in football or in life, difficult starts and adversity—even the self-imposed variety—don’t have to result in devastation.

And he’d get a high-five on that from teammate Virgil Green, a tight end.

Colquitt and Green are both believers in Christ who look back to troubling times in their college days being turning points that God used to draw them much closer to Himself.

For Colquitt, it was a matter of falling into the party scene at the University of Tennessee that belied his Christian upbringing.

For Green at the University of Nevada, it was a health scare—a risky knee surgery that could have prevented him from ever making it into the NFL.

In both cases, they turned aggressively toward the Lord and have been delivered by His faithfulness.

Colquitt, with the witness of his parents and Tennessee coach Phil Fulmer, repented of his sins and recommitted his life to Christ.

“Looking back, I wasn’t active in the Word and growing in my spirit at that time, so I let the flesh take control,” he said. “I try to be on the other side of that now, to stay in the Word and do whatever I can to keep Him close and to stay in prayer.”

One of Colquitt’s primary aims now is to be a God-honoring spiritual leader of his family. He and his wife Nikki have three young children, ranging in age from 2 ½ weeks to 4.

“I try to focus on the audience of One because, otherwise, it’s so easy to get distracted,” Colquitt said. “If you’re in a stadium with all those people, and many more watching on television, it’s easy to say, ‘I’ve got to please all these people.’

“But when it really comes down to it, God is my only audience. It’s not about performance or anything like that. It’s about your heart. So you can turn it into an act of worship because He’s called for everything we do in life to be a matter of worship, including sitting at the table having dinner with your family.”

Green’s knee condition was like that of a much older person during only his freshman season at Nevada. He underwent microfracture surgery to help slow degenerative cartilage damage.

He was told that he might never play football again.

His parents, who were strong Christians, prayed for and supported him, but it was at that time that Green realized he had to go forth in his own faith and fully surrender his life to the Lord.

“It really helped mold my faith and show me that God is real,” Green said.

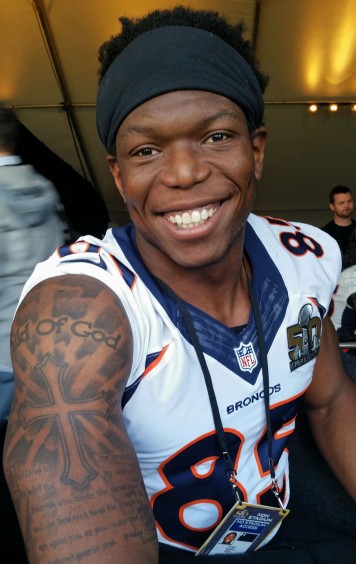

Now, more than eight years later, he has experienced an almost total healing in his knee. He’s a valued blocker in the Broncos’ offense from the tight end and fullback positions and has scored one touchdown as a receiver.

“The Lord means everything to me,” Green said. “I understand the platform that I’m on, and I never would have made it to this point without Christ.

“I like to work with kids and tell them: ‘You don’t have to follow what the world wants you to do. Christ has everything you need.’ That’s what I stand firm on.”

Green has part of Psalm 121 tattooed on his right arm because he loves the passage that answers the question “Where does my help come from” with “My help comes from the Lord, the Maker of heaven and earth.”

Colquitt feels the same way. He comes from a family of punters: his father Craig filled the role with the Pittsburgh Steelers’ Super Bowl championship teams of the 1970s and his brother Dustin punts now for the Kansas City Chiefs. They’ve all learned only God provides what football and championships could never deliver.

“When it’s all said and done, these things are going to be gone,” Britton Colquitt said. “What matters is [eternal] life and what we’re doing in this life to prepare for that.”