This article was originally published in January 2020.

At 6:01 p.m. on April 4, 1968, a shot rang out. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who had been standing on the balcony of his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, now lay sprawled on the balcony’s floor. A gaping wound covered a large portion of his jaw and neck.

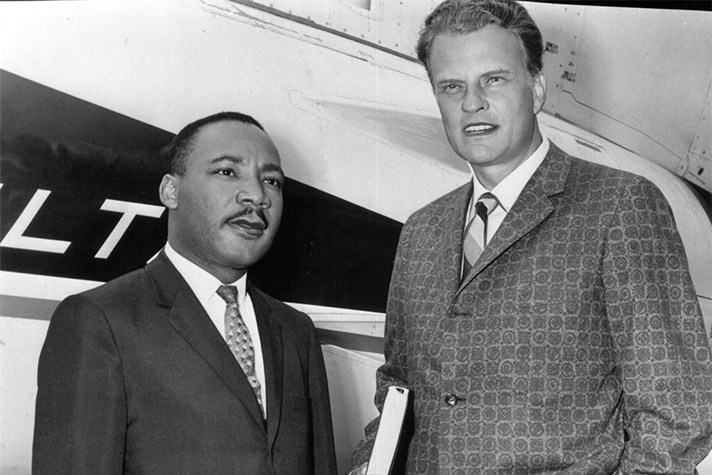

Billy Graham was in Australia at the time of Dr. King’s death. He remembers the moment someone approached him with news of Dr. King’s assassination, which was followed by journalists seeking a quote: “I was almost in a state of shock. Not only was I losing a friend through a vicious and senseless killing, but America was losing a social leader and a prophet, and I felt his death would be one of the greatest tragedies in our history.”

Describing how he met Dr. King during a 1957 Crusade meeting in New York City, Mr. Graham writes in his autobiography, “One night civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whom I was pleased to count a friend, gave an eloquent opening prayer at the service; he also came at my invitation to one of our Team retreats during the Crusade to help us understand the racial situation in America more fully.”

As their friendship grew, Dr. King asked Mr. Graham to call him by his nickname. “His father,” explains Graham, “who was called Big Mike, called him Little Mike. He asked me to call him just plain Mike.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. entered the Christian ministry and was ordained in February 1948 at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta at the age of 19. In 1954, upon completion of graduate studies at Boston University, he accepted a call to serve at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama.

While there, Dr. King was an instrumental leader in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, made famous by the nonviolent resistance and arrest of Rosa Parks. He resigned from Dexter Avenue Baptist in 1959 to move back to Atlanta to direct the activities of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

From 1960 until his death in 1968, he also served as co-pastor with his father at Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Dr. King credited Mr. Graham with having a significant part in reducing the tension between whites and blacks in the South. In 1965, Mr. Graham canceled a tour of Europe to preach a series of Crusades in Alabama, praying that the Gospel would tear down walls of division between the races and seeing the importance of his work alongside Dr. King’s.

Dr. King later said, “Had it not been for the ministry of my good friend Dr. Billy Graham, my work in the Civil Rights Movement would not have been as successful as it has been.”

During the Civil Rights Movement, Mr. Graham preached: “Jesus was not a white man; He was not a black man. He came from that part of the world that touches Africa and Asia and Europe. Christianity is not a white man’s religion, and don’t let anybody ever tell you that it’s white or black. Christ belongs to all people; He belongs to the whole world.”

Reflecting on how his thinking changed through the years, Mr. Graham writes, “I cannot point to any single event or intellectual crisis that changed my mind on racial equality. At Wheaton College, I made friends with black students, and I recall vividly one of them coming to my room one day and talking with deep conviction about America’s need for racial justice.

“Most influential, however, was my study of the Bible, leading me eventually to the conclusion that not only was racial inequality wrong but Christians especially should demonstrate love toward all peoples.”